Dreaming of Oasis (2021)

Stephanie Cuyubamba Kong BFA thesis spring 2021

dreaming of greener grass #1-6 (Dreaming of Oásis)

Dreaming of Oasis imagines a world where euphoric and fantastical joy resides. It manifests itself in the landscape, calling us to join in its utopia-esque liveliness. This two-part photographic series explores the ideology of Oasis as an escapist fantasy, what it represents, and perhaps, what it falsely promises us. In theory, Oasis is a place of refreshment, of vital nourishment, of what you need but didn’t know you wanted. Oasis also acts as a corner store – it supplies what is missing, filling an unwritten void. It is the fluorescent glow of a 99-cent Arizona in the window, tempting, ready to quench one’s thirst.

These photographs bear arms of lush visual language, using artificial flora and decaying produce to create decadent and inviting landscapes that reflect the complexity of building utopia. Across six images an island rises out of the water; its banks are built of oxidized guacamole and streams made of candy pink Duvalín that flow over dragonfruit slopes, growing whimsical multicolor trees and pearls. Some are dead, but others are artificially alive; signifying the passage of time and acknowledging that even in utopia not all life is evergreen.

By referencing and conversing with the canon of the landscape photograph; these images also argue against the dominance of a possessive, white, male gaze over the genre. Since reading “Landscape and the White Gaze” by Martin Berger I have been questioning if, in retaliation against the colonial white gaze, there could ever be such thing as a restorative brown gaze – and I’m still not sure if this is possible. After much experimentation in found landscape photography, I felt myself being drawn back into the constructed image, where I could control every aspect of the work. This made agency in the authorship of each image essential; as I found it necessary to be heavy-handed in the construction and aesthetic of place in opposition to the colonial fantasy of untouched, prevailing wilderness. The struggle for dominance over land and people is at the center of the colonial white gaze, and to undermine this mode of image-making I decided to build a landscape that can never be touched (the construction was perishable, and therefore had to be thrown away after being photographed). To drive this idea further, each photograph is obscured by a green leaf with little holes through which to peep. Now the viewer must become aware of their voyeuristic, invasive gaze, hopefully prompting them to realize how complicit we can be in the act of othering.

In this new series, I am thinking about what the oásis might look like, what it signifies, and what it can be. Ideologically, the oásis (purposefully spelled with the tilde) is a place of refreshment, of vital nourishment, of what you need but didn’t know you wanted. In theory, the oásis is a bodega as well - it supplies what is missing, and fills an unwritten void. Through this visual investigation, I hope to re-imagine what oásis could look like, what it can represent, and even what it falsely promises us.

The use of exotified produce, often acquired at the cost of demanding and exploitative human labor, and long-standing metaphors of exotic fruits for the bodies of brown women1 have grossly commodified the relationship between identity and landscape. These complexities question how we perceive this imaginary Oasis, and by building fantasy on a rotting foundation (visually and metaphorically), I am inviting the viewer to wonder why we dream of escaping when our world feels as if it is crying out in despair. These bodegónes offer the viewer a voyeuristic peek into this imagined place, holding utopic Oasis at an arm’s length, not quite ready to give in to the promise of greener grass on the other side. In these images, the consumable and perishable materials are reclaimed – not to champion marginal identity for the purpose of remaining othered, but rather to create space for alternative oases to emerge. Dreaming of Oasis’ bodegónes challenge our reliance on escapist fantasies, offering alternative to the idea of utopia through the vernacular of our lived identities.

The viewer may ask why the fantastical and imaginary world is centered in this work, if my concerns are with the burden and pain of our mundane, IRL experience. To this, I respond that the job of the artist is to guide us to possibilities más allá. That is to say; possibilities drenched in beauty, temptation, and glory so that we might be persuaded to follow its vision for the future.

1. Tu terrón de sal/Un rayo de sol/Que donde digas que tú/Quiera que yo vaya voy/eres mi desliz, mi páis feliz/Mi primavera/Mi escalera al cielo si/Por eso sigo aquíy camino

(24 x 30 in. Ink on archival satin paper, framed, 2019)

2. Under the glare of the highland sun, a quiet glory falls upon my heart/persisting

(24 x 30 in. Ink on archival satin paper, framed, 2020)

3. Vamo’ a hacer maldade’/No le pare y dale/Baby, cuida’o por ahí (por ahí)/Que eso se te sale, que eso se te sale

(24 x 30 in. Ink on archival satin paper, framed, 2019)

4. Remnants of joy, life, and rejuvenation take on new life as the sun rises/imbued with a strange sense of calm in their stillness

(24 x 30 in. Ink on archival satin paper, framed, 2021)

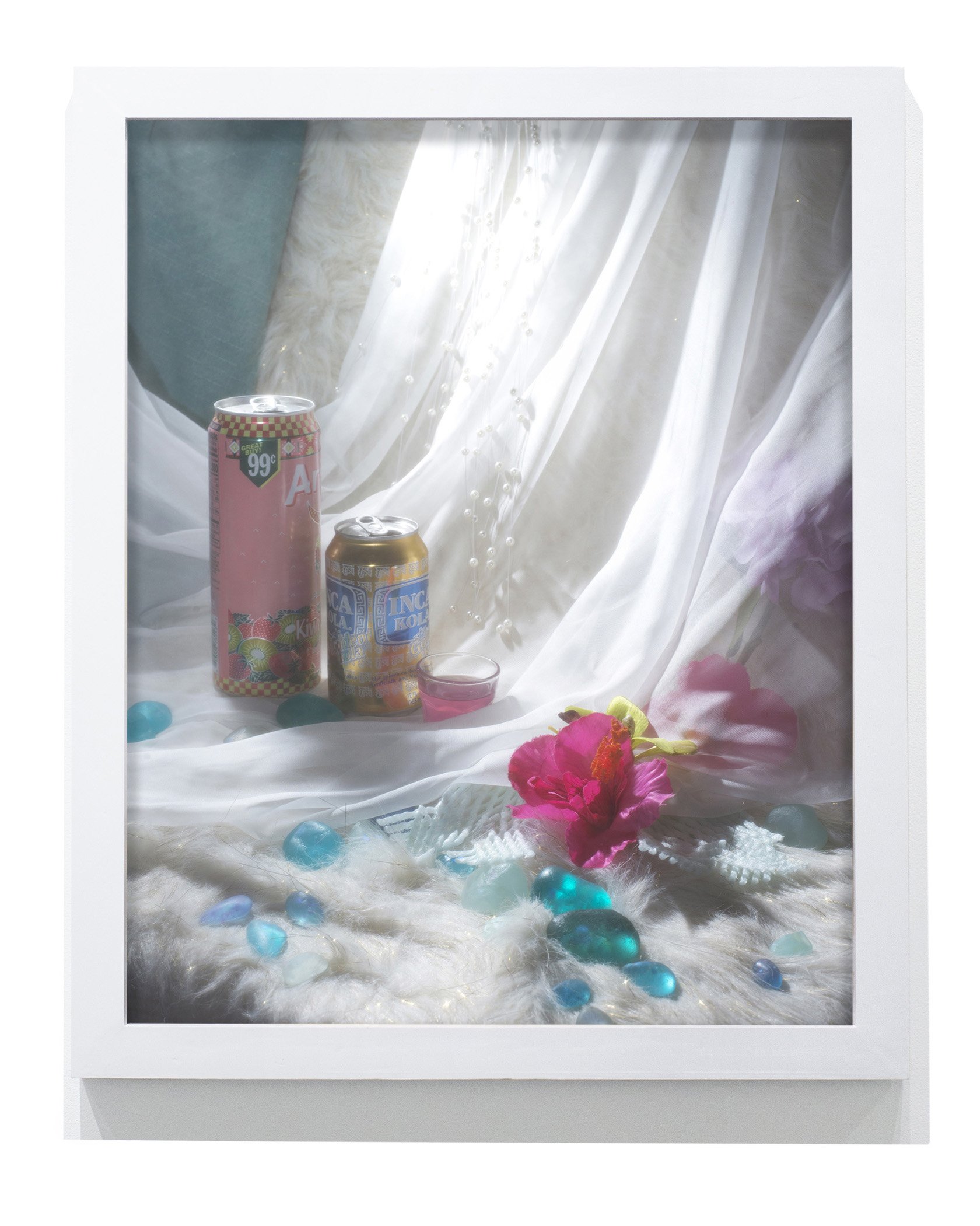

In four large, still-life-like photographs, I invite the viewer to dream of an Oasis closer to us, perhaps existing in this world, built by things already part of our cultural vernacular. In this still life series, I use specific objects and visual language to describe a life – my life – lived at the intersection of memory, family, food, and music of my time. My lived experience as a first-generation latine caught across cultures is reflected in these images; images that function as tableaus of a place situated between here and utopia, heaven made up of things we already have, a reachable and no-so-far-away place.

Cans of Inca Kola, Arizonas, crumbs, plastic imitation cut crystal, and other material sit nestled amongst lace and silks. Swathed in light, these images elevate objects of my cultural vernacular to a status of beauty and glory that I believe they deserve. Lighting in three out of four of these images [Tu terrón, Under the glare, Vamo’ a hacer maldade’] is used to illuminate and present each arrangement. In contrast, the fourth image [Remnants of joy] is intentionally more difficult to discern, being filtered through a warm haze that separates viewer from objects, in an attempt to move them from this world into the imaginary.

The first series of still lifes created for this thesis were inspired by the ideas presented in Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands, which proposes that we define our mestiza, in-between identities by our lived experiences; as those will always be more correct than any historical or ancestral account of what we were supposed to be. (Anzaldúa 2003) Because western colonization (and for me specifically, the Spanish conquest of Latin America including Peru) disrupted so violently our formation of identity, we must rely on our lived realities to construct selves from the ashes of indigeneity and empire.